“I am stuck here. I also know the situation and crisis my employer is passing through, but right now, Lebanon is a prison to me.”

These are the words of Tigets, a migrant domestic worker from Ethiopia who hasn’t seen her son since she left for job in Lebanon four years ago.

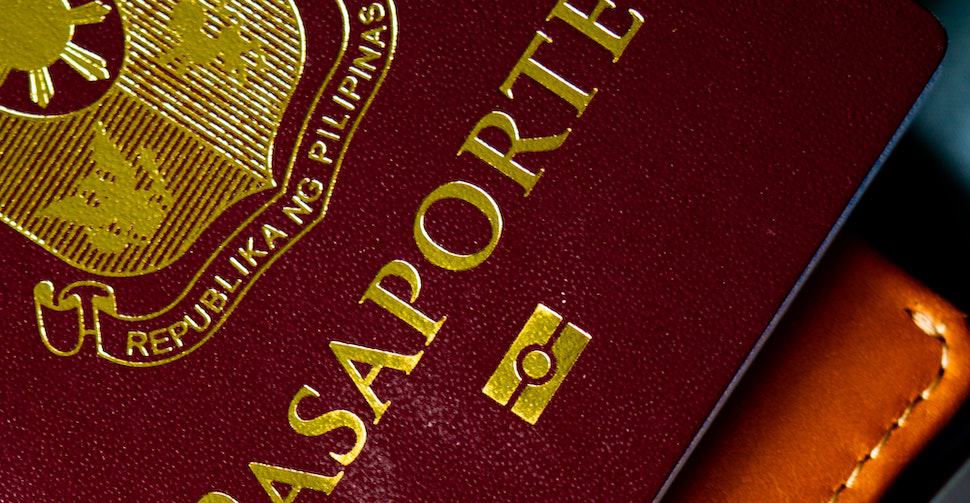

Lebanon’s economic crisis has had devastating effects on migrant domestic workers. With their employers out of work, many haven’t been paid in years. Even if their work contracts have ended, many domestic workers can’t afford to buy a plane ticket home and those that can often don’t have access to their passports since their employers confiscated them. In short, Lebanon has become a purgatory.

L’Orient Today reports:

Repatriation had become a growing demand among migrant workers in Lebanon since the country’s sprawling economic crisis began two years ago, particularly after hundreds were abandoned by their employers, tossed out in front of their consulates, often with no money, food or even their official documents.

However, a number of obstacles stand in the way of many people’s ability to return, including ticket prices, unpaid previous salaries and official documents that are withheld by employers.

Another Ethiopian woman, who asked not to be named, told L’Orient Today that her employers had kicked her out because they can no longer afford to pay her salary, “I am not able to buy tampons or pads, and I can’t even afford to buy basic food. I try to sleep most of the time so that I don’t have to through feeling starved,” she said, explaining that she is currently staying with friends.

“I want to go back to my country so that I can try and find a job somewhere else … anywhere but here,” she said.

Before the economic crisis, there were an estimated 200,000 migrant domestic workers in Lebanon, working under the oppressive kafala sponsorship system where they are tied to a specific employer and do not have the same rights as other employees under labor laws.

Some local NGOs and embassies are stepping up to help. Egna Legna Besidet, a Lebanon-based Ethiopian migrants’ rights organization, has helped 20 Ethiopian women return home and the Philippine embassy has announced that it would repatriate 280 “undocumented and distressed” workers.

In 2020 there were glimmers of hope for reform when Labor Minister Lamia Yammine issued a new labor contract that allowed workers to terminate their contract without the consent of their employer at a month’s notice, guaranteed them the national minimum wage, and explicitly forbid employers from confiscating workers’ passports. Yet pushback from recruitment agencies and the Shura Council, the country’s top administrative court blocked its implementation.

With Lebanon’s formation of a new government, campaigners hope there will be change. “With the new government, we hope that the new minister of labor would not just push for a new, humane system regarding domestic migrant workers,” said Diala Haidar, Amnesty International’s campaign officer in Lebanon.

Freedom United is interested in hearing from our community and welcomes relevant, informed comments, advice, and insights that advance the conversation around our campaigns and advocacy. We value inclusivity and respect within our community. To be approved, your comments should be civil.