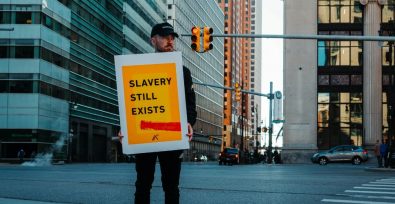

Many anti-trafficking groups are still fighting modern slavery through rescue efforts. But what if this approach does more harm than good? As explored in a blog by openDemocracy, rescue organizations rely heavily on stories with sensationalist language and images of helpless victims for fundraising—a strategy that strips survivors of their agency and dignity.

A growing number of activists and researchers say it’s time for change. They argue that the fight against trafficking should focus less on “rescue” and more on real solutions that consider the many nuances of exploitation.

What’s wrong with rescue?

Campaigns surrounding “spot the signs” often simplify complex situations. But real life is rarely so clear. These campaigns rely on dramatic stories—images of people chained, bruised, or crying. But this can mislead the public. Most exploitation doesn’t look like that. It also creates a system where people must prove they’re ‘victims’ to get help. If they don’t fit the stereotype, they may not be supported by stakeholders.

Additionally, public identification can have serious consequences. For example, sex workers being outed in their communities. For others, it leads to legal risks, particularly when there are no safeguards between immigration authorities and services like healthcare, education, or employment.

In the UK, people are often referred to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), the system used to identify modern slavery cases, without being told that their information may be shared with the Home Office. This lack of transparency puts them at risk of immigration enforcement or even deportation.

Why the ‘victim’ story persists

So why does the ‘victim’ narrative continue? Because it still works. Civil servants, authorities, and third sector advocates and activists use the ‘victim’ narrative to bring in donations, media attention, and government support.

In the UK, for example, victimhood narratives help counter public mistrust fueled by anti-immigration politics and the criminalization of young people. These stories draw in donors, who often provide funding and basic support where the state has failed to step in.

Research done in the UK between 2017 and 2020 showed that faith-based rescue organizations were aware of the way victimhood language dehumanizes survivors. One organization admitted:

“It’s just a more emotive word. I still use the word victim even though it [assumes powerlessness], when I need people coming on my side… and that’s usually within the [local authority] housing team, or with benefits.”

Another said putting a man on the cover of a magazine hurts fundraising:

“Put a man on the front of our magazine and our donations will drop.”

The story of a damsel in distress pulls on emotions—and wallets. But it also creates a “hierarchy of sympathy.” A trafficked woman gets help. A migrant fruit picker does not.

This shows how prevalent hierarchical victimhood is in society and the dangerous decisions organizations make to secure funding.

Shifting the story from ‘victim’ to ‘survivor’

Change is happening. More anti-trafficking groups now use the term ‘survivor’ to highlight strength and agency. In 2018, the UK published the first Trafficking and Modern Slavery Survivor Care Standards focused on empowerment. The Office for Victims of Crime in US is in the process of doing the same.

In 2025, global ethical principles were created to guide how NGOs share stories and images of trafficking. In fact, openDemocracy uses Freedom United’s My Story My Dignity pledge which is close to meeting our target of 30,000 individuals, companies and institutions who pledge to represent survivors with dignity. This pledge was created in collaboration with Unhidden, a photography project to produce alternative images of journeys into and out of modern slavery. This project was developed into content guidelines training with Freedom United, supporting uptake by UK anti-trafficking leaders.

The goal is to stop commodifying suffering. The author writes:

“Anti-trafficking cannot commodify suffering without replicating exploitation. It therefore must remain a priority to abandon victimhood. A pragmatic, prevention-focused and effective response to severe exploitation requires building solidarities with the movements tackling complex causes.”

We must demand better for survivors

Despite some progress, the pressure to raise funds keeps many anti-trafficking organizations tied to outdated rescue narratives. The ‘victim’ story is easier to sell—but there’s a better way. It starts by listening to survivors, respecting their voices, and investing in prevention and stronger systems.

Donors and the public have a role to play, too. By demanding ethical storytelling and supporting dignity-first approaches, we can build a movement that empowers—not dehumanizes.

Take action and sign Freedom United’s My Story, My Dignity pledge.

Read why our Executive Director believes it’s time to move beyond the rescue model here.

Freedom United is interested in hearing from our community and welcomes relevant, informed comments, advice, and insights that advance the conversation around our campaigns and advocacy. We value inclusivity and respect within our community. To be approved, your comments should be civil.