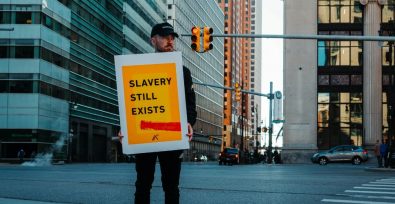

In her insightful Open Democracy article, Judy Fudge unpacks the growing popularity of forced labor import bans—and urges us to think twice before praising them as an easy fix for exploitation in global supply chains.

Forced labor import bans allows customs officials to stop goods at the border if they suspect the supply chain used forced labor. Governments in the global North—including the US, Canada, and Mexico—have embraced them, and the EU is moving in the same direction. At first glance, these bans look like a strong stand against modern slavery. But as Fudge argues:

“Before we jump on the ban wagon, we should pause to consider some of the lessons labour advocates have learned from observing over 20 years of enforcing anti-trafficking-law. These include: the impact of the provenance of governance instruments on their effectiveness; the ways instruments are used for a range of political ends; the ways they create collateral damage; and how their use lends them legitimacy, even when they are deeply flawed.”

Protecting workers—or just markets?

Fudge reminds us that forced labor import bans are hardly new—they have deep roots in trade protectionism. Section 307 of the 1930 US Tariff Act, the earliest of these bans, was not designed to stop human trafficking but to “protect US producers and US workers from being undercut by foreign suppliers who were importing goods made cheap by forced labour.” For decades, this section went unenforced until the Obama administration closed a loophole in 2015.

Under the Trump administration, Section 307 resurfaced itself as part of an “America first” agenda, targeting Chinese imports in particular. One of the clearest examples is the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), passed in 2021.

Meanwhile, the EU’s ban passed in 2023 reflects both worries about China’s growing influence and pressure from civil society. As Fudge writes, “States in the global North are designing and enforcing forced labour bans with the primary aim of protecting their own markets and workers.”

Civil society’s dilemma

Why do so many labor and human rights groups support these bans if their main function is economic self-interest? Fudge gives two main reasons: people feel frustrated with voluntary corporate social responsibility schemes that fail to stop exploitation, and they hope to strengthen bans over time. She explains that import bans can “place significant commercial pressure on companies to address forced labor in their supply chains or risk losing access to valuable export markets.”

However, the reality on the ground is more complicated. The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) enforces Section 307 through Withhold Release Orders (WROs). The vast majority target foreign suppliers. According to the article, between June 2022 and December 2024 alone, the CBP detained over 12,000 shipments worth $3.68 billion under the UFLPA. However, nearly half of these shipments were later released, showing how easily bans can be bypassed.

The risks for workers are serious. Companies facing a WRO can simply cut ties with suppliers to avoid penalties. This might appear to punish bad actors—but as Fudge states:

“There is nothing to stop a lead firm in a global supply chain from simply cutting ties with a supplier who has been issued a WRO. Some might say that’s the whole point – exploitative firms should be starved of contracts until they close – but without a safety net, workers are sacrificed under this approach. They lose their jobs and wages with no guarantee that their next employer (if there is one) will be any better.”

Additionally, she also points out that customs officials have complete discretion in enforcement and are not required to consult the workers whose rights are supposedly being defended.

A cautionary lesson

As Fudge reminds us,

“20 years of watching countries enforce human trafficking laws has demonstrated the need to consider the different goals legal instruments are supposed to achieve, how they are actually enforced, and their unintended consequences before choosing what to endorse.”

For campaigners, policymakers, and concerned citizens alike, the lesson is clear. Forced labor import bans might be an important tool—but they are not nearly enough. Without safeguards for workers, they risk prioritizing market protection over human rights. That is why we advocate for policies that genuinely, not performatively, put people before profit.

Freedom United is interested in hearing from our community and welcomes relevant, informed comments, advice, and insights that advance the conversation around our campaigns and advocacy. We value inclusivity and respect within our community. To be approved, your comments should be civil.