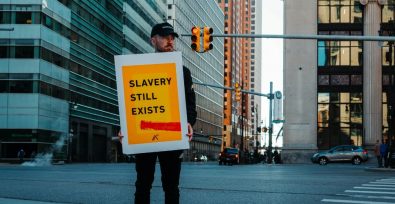

Most people think slavery is a practice that ended with abolition laws. Yet, as Jasmin Gallardo shares, abolition laws focused on ending legal ownership, not on dismantling the economic structures that depended on exploitation. That gap created space for forced labor to reemerge in forms that were technically legal, harder to see, and easier to defend.

The systems that drove slavery were never dismantled

In many places, formerly enslaved people were released without land, income, or legal protection, leaving them with few viable choices but exploitative labor arrangements. Plantation owners, industrialists, and governments quickly adapted, ensuring forced labor remained central to economic life.

In the US, sharecropping tied Black families to land through cycles of debt that were difficult to escape. In colonial territories across Africa and Asia, European powers imposed labor taxes that compelled local populations to work on plantations and infrastructure projects. These arrangements were framed as contracts or civic obligations, yet refusal often led to imprisonment or violence.

Incarceration and colonial rule recreated forced labor

After slavery was abolished, Southern states in the US targeted newly freed Black populations with laws known as Black Codes. These laws criminalized everyday behavior such as loitering, unemployment, or failing to carry proof of work. Arrests surged, feeding a system of convict leasing.

For MSN, Gallardo writes,

State governments leased prisoners to private businesses, plantations, railroads, and mines, generating revenue while absolving themselves of responsibility for prisoner welfare. Unlike enslaved people, who were considered valuable property, leased convicts were expendable. Death rates were extraordinarily high due to brutal working conditions, starvation, and violence. This system effectively recreated slavery under the protection of the law, using incarceration as justification.

Beyond the US, colonial governments enforced forced labor while publicly condemning slavery. Indigenous populations were compelled to work on roads, railways, plantations, and mines to pay taxes that could only be settled through labor.

Modern economies still rely on coercion

Forced prison labor is one of the clearest modern continuations of slavery. In the US and elsewhere, incarcerated people are often forced to work for little or no pay under threat of punishment, loss of privileges, or extended sentences. Excluded from standard labor protections, they work in unsafe conditions for the financial benefit of large corporations. Just last week, lawmakers in New Hampshire advanced a bill to subject people convicted of certain crimes hard labor for life.

Forced labor also thrives in global supply chains. Forced labor often occurs at the lowest levels of production, far from consumers and oversight. Corporations benefit from this distance, claiming ignorance while continuing to profit.

Debt bondage traps workers through recruitment fees and loans that can never realistically be repaid. These debts are often inherited, binding families across generations.

Human trafficking operates through deception, document confiscation, threats, and fabricated obligations, forcing millions into labor, sexual exploitation, or domestic servitude. Migrant workers are particularly vulnerable, especially when immigration systems tie legal status to employers.

Help us end this!

Slavery has survived by adapting. This is exactly why the Freedom United exists. Ending modern slavery requires constant pressure to expose exploitation, challenge policies that normalize coercion, and hold systems accountable wherever forced labor reappears. Your support helps ensure freedom is not merely promised, but practiced.

If you’re able, please consider making a small donation to help keep us going.

Freedom United is interested in hearing from our community and welcomes relevant, informed comments, advice, and insights that advance the conversation around our campaigns and advocacy. We value inclusivity and respect within our community. To be approved, your comments should be civil.